Public domain - Source: Boeing

|

|

Public domain - Source: Boeing |

Apollo launch commences at Kennedy Space Center at Cape Kennedy, Florida ( Now Cape Canaveral)

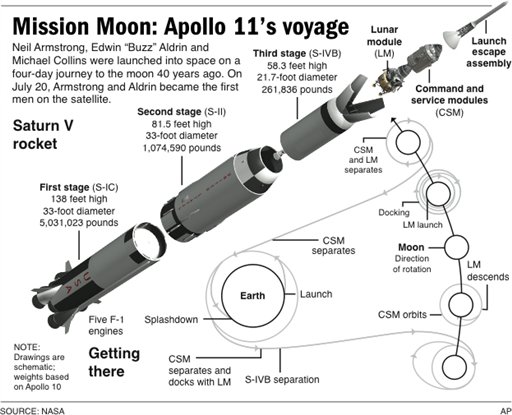

Preparation starts weeks before launch, but the final count down starts 13 hours before lift off. The propellant and oxidiser tanks are filled and the crew run through the mission checklist.The first stage ignition sequence started 8.9 seconds before the launch.

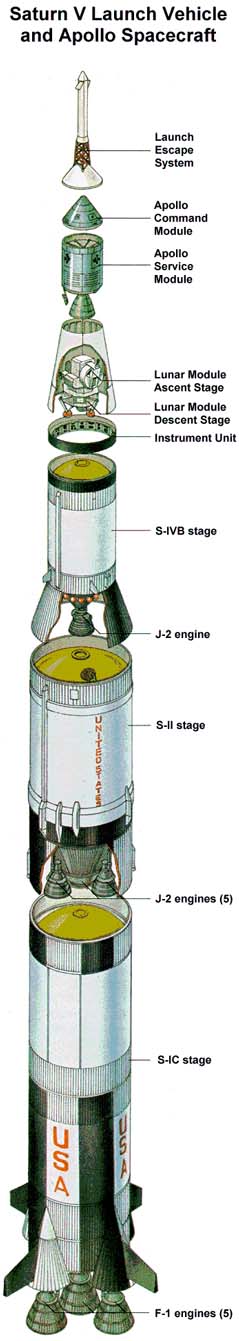

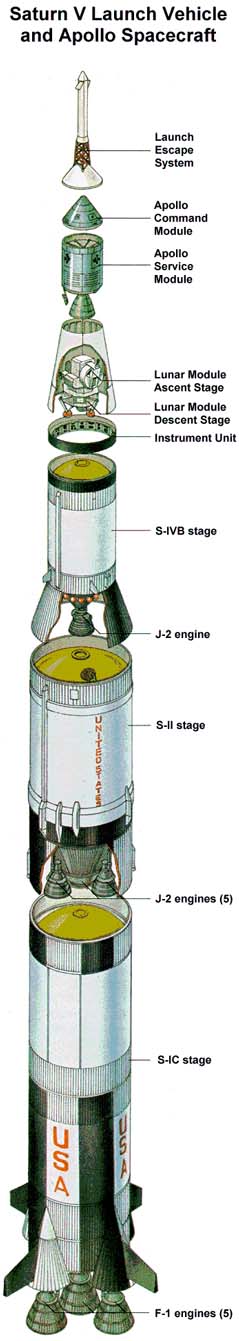

The five F-1 kerosine fuelled rocket engines of the Saturn V launch vehicle each with a thrust of over 1.5 million pounds, fire 0.3 seconds apart to lessen resonance effects in the fuel system which could cause "pogo stick" like vibrations on the rocket's structure and systems as well as on the astronauts, and Apollo 11 slowly rises from the launch pad taking 11 seconds to clear the launch tower.

S-1C powered flight with a thrust of 7.6 million pounds from the five F-1 engines gulping 13 tons of kerosene (RP-1) and liquid oxygen (LOX) per second, pinning the astronauts into their seats with a "g" force of 4.5 g.

Two miles off the launch pad and travelling at 1500 mph, Saturn's guidance computer sets Apollo 11 on the planned trajectory with directional adjustments being made by means of hydraulic actuators on the gimbal mounts of the four outer F-1 engines.

Loss of control during the critical launch phase would result in the destruction of the rocket. Such an event would however trigger the Launch Escape System to eject the crew capsule and deploy its parachutes to bring the crew safely back to the ground.

Mission Control Center (MCC) in Houston track the spacecraft throughout its mission, except when it is behind the Moon during which communications are not possible. The timings and duration of the engine burns at key points are controlled by MCC Houston and are programmed into the Guidance Computers in the Instrument Unit, the Command Module and the Lunar Module.

After 2.5 minutes the 4.5 million pounds of propellant in S-1C is used up and retro rockets fire to separate it from the S-11. The S-1C is jettisoned and falls into the Atlantic Ocean. By that time, Saturn V has reached an altitude of 45 miles, 350 miles downrange and is travelling at 6,300 mph

Four seconds later the five J-2 hydrogen fuelled engines of the S-11 start up.

Two solid motor retrorockets were located inside each of the four conical engine fairings. At separation of the S-IC from the flight vehicle, the eight retrorockets are fired, blowing off removable sections of the fairings forward of the fins, and backing the S-IC away from the flight vehicle as the engines on the S-II stage are ignited.

S-11 powered flight with a total thrust of 1.125 million pounds from the five J-2 engines.

Once the second stage is safely on its way, at a height of 60 miles, the launch escape tower is jettisoned.

After 6.5 minutes the 942,000 pounds of propellant in Stage 2 are exhausted. The S-1VB Stage 3 takes over and the S-11 is jettisoned.

By that time Saturn V has reached an altitude of 110 miles, 1400 miles down range travelling at 15,000 mph

S-1VB powered flight with a single J-2 re-startable engine with a thrust of 225,000 pounds.

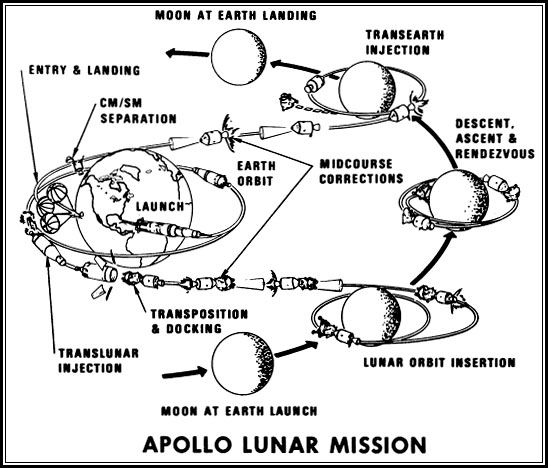

The J-2 engine burns for 2.5 minutes to put the Saturn V into a parking orbit 1,640 miles downrange at an altitude of 118.8 miles (191.2 km) with an orbital velocity of 17,432 mph. The third stage remains attached to the Apollo 11 spacecraft while it orbits the Earth two and a half times while astronauts and mission controllers check that all systems are functioning correctly and prepare for translunar injection.

After one and a half Earth orbits, the Saturn's third-stage J-2 engine is re-started to produce a second burn lasting 6 minutes which accelerates the Apollo 11 to an altitude of 190 miles with a velocity of 24,500 mph (10.9 kms/sec) to escape from its Earth parking orbit and enter into a "free return trajectory" to the Moon. This means that when the spacecraft eventually passes by the Moon its velocity, direction and radial distance from the Moon will be such that the Moon's gravity will deflect it into a "slingshot" path around the Moon and back in the direction it came from towards the Earth. Too close or too slow would cause the spacecraft to crash into the Moon. Too far away or too fast would send the spacecraft on a one way journey into space.

To complicate the manoeuvre even further, the Moon is a moving target travelling at 2286 mph orbiting the earth in 27 days so that the direction of the spacecraft as it leaves the its Earth orbit is not to where the Moon is at the instant of departure, but to where it will be in three day's time when the spacecraft actually reaches it. This requires very precise control over the point, or timing at which the spacecraft leaves the Earth orbit and the duration of the engine burn.

Note that the velocity necesary to overcome from the Earth's gravitational pull depends on the spacecraft's orbital altitude. At the Earth's surface the escape velocity is slightly higher at 25,000 mph (11.2 kms/sec).

Apollo 11 begins its three-day, 240,000 mile unpowered flight through the vacuum of space to the moon.

During its transit through the atmosphere the flimsy Lunar Module (LM) sits on top of the Saturn V third stage inside the LM Adapter which protects it from damaging aerodynamic forces. Then during the first 10 minutes of the translunar coast, when Apollo11 is above the Eath's atmosphere, the attitude of the spacecraft is adjusted in readiness for extracting the Lunar Module from the LM Adapter and coupling it to the CSM.

The Service Module has sixteen reaction control thrusters, small rocket engines each with a thrust of 100 pounds, to control its attitude and translation movements along its three axes, for course corrections, rendezvous, and docking manoeuvres. They are mounted in sets of four "quads" spaced 90 degrees apart around the circumference of the Service module. The Command Module also has 12 thrusters for the same purpose.

The next three steps are the Lunar Module Transposition and Docking

|

|

Public domain Lunar Module Transposition and Docking |

The panels of the LM Adapter are jettisoned and the reaction control thrusters of the CSM mother ship are fired to separate it from the Saturn S-1VB third stage, leaving the Lunar Module behind and stopping 50 to 75 feet away.

The CSM thrusters now rotate the CSM by 180 degrees and dock it with the Lunar Module which is still attached to the third stage. All this happens with the Saturn S-1VB and the CSM hurtling separately through space at over 24,000 miles per hour.

The third stage S-IVB, together with the Instrument Unit is jettisoned, and go into orbit around the Sun.

After 4 hours and 40 minutes into the flight, the LM is now docked with the CSM mother ship and ready for its journey to the moon.

|

|

|

© Mark Wade Lunar Module Docked with Command and Service Modules |

The CSM and LM continue their three day journey to the Moon tracked by mission control in Houston. Travelling through the vacuum of space, the flimsy Lunar Module no longer needs the protection of the LM Adapter. During this phase of the journey the spacecraft is put into a slow roll of two revolutions per hour to provide uniform solar heating, however this is stopped during navigation sightings and course corrections.

Still influenced by the Earth's gravitational pull, the spacecraft gradually slows down to about 2040 mph at 39,000 miles from the Moon but as the Earth's gravitational effect continues to weaken, the Moon's gravity begins to dominate and the spacecraft speeds up again to about 5600 mph until it is eventually pulled into a "slingshot" trajectory around the back of the Moon.

Mid-course corrections to to ensure that the spacecraft does not stray from its "free return trajectory" are implemented by either, or both, the Service Module's reaction control thrusters or by its main propulsion engine.

Besides the mid-course correction, during the flight, the crew periodically checks their position with respect to the stars using a sextant and this celestial reference is used to correct for any drift of the gyroscopes in the inertial navigation system.

Although the Apollo 11 had autonomous navigation and control systems, it still needed constant communications with Mission Control in Houston since it did not have sufficient computing power at all times to monitor the spacecraft's speed and position in space and to program the timing and duration of the main engine and control thruster burns to make any course corrections necessary to initiate lunar orbit insertion or to get the spacecraft back to Earth in an emergency.

But communications. between the Earth and the spacecraft need a "line of sight" link between the transmitters and the receivers and this raises potential problems at both ends of the link.

While in luinar orbit, the Apollo 11 spends 45 minutes behind the moon, during which time communications with the Earth are not possible. At the other end of the link the Earth is rotating and part of the time the Mission Control Center in Houston is facing away from the Moon and unable to "see" the spacecraft.

To address the first problem the spacecraft receives targeting information from Houston before each loss of signal as it passes behind the Moon. If acquisition of the signal fails when it emerges from behind the Moon, the landing will be scrubbed and the crew will use that information to target a contingency burn home.

To maintain communications with the spacecraft as the Earth rotates, at least three satellite ground stations separated by approximately 120 degrees of longitude and connected by a terrestrial network to Mission Control are required so that as the Earth turns the spacecraft is always above the horizon of at least one station so that there id no loss of signal due to the Earth's rotation..

To breakout from its slingshot track around the Moon and enter into lunar orbit, a retro-thrust is required to slow the spacecraft down from its velocity of around 5,600 mph, with respect to the Moon's velocity, to 3,600 mph allowing it to be captured by the Moon's gravity. Due to the ballistics of the slingshot trajectory around the Moon, this manoeuvre must take place while the spacecraft is behind the Moon and out of communication with the Earth. Thus after loss of signal as Apollo 11 passes behind the Moon and the Service Module fires its main propulsion engine in two burns in the direction of travel to slow its momentum and enter lunar orbit. The first burn lasts 6 minutes and places the craft in an initial elliptical lunar orbit of 196 X 69 miles. The second burn lasts just 17 seconds and eases Apollo 11 into a circular orbit of 69 miles, in preparation for Lunar Module separation and powered descent. Using two shorter burns reduces the chance of overburn, which would slow the spacecraft too much causing it to crash into the lunar surface.

The CSM docked with the LM, travelling at 3,600 mph at an altitude of 69 miles, continues orbiting the Moon once every two hours during which time it is out of communication with the Earth for 45 minutes. During 13 orbits the crew check that all systems are functioning correctly, make observations of their planned landing site in The Sea of Tranquility and also spend some time resting.

The LM pilots, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin transfer from the Command Module to the crew compartment in the Ascent Stage of the LM and check that all systems are performing correctly.

Using its reaction control thrusters the LM undocks from CSM to prepare for descent while Michael Collins in the Command Module makes a visual check of the LM landing gear.

Because the Moon has no atmosphere it is not possible to use parachutes to make a soft landing and a powered descent to the lunar surface is needed. The descent to, and ascent from, the Moon are both controllled from the LM crew compartment in the Ascent Stage which contains the necessary status displays and control systems. A single set of 16 reaction control thrusters, identical to those used on the Service Module, to control both the descent and ascent is also mounted on the Ascent Stage of the LM. However the LM Ascent and Descent stages each have their own main engines, the descent engine with a thrust of 10,125 pounds being much larger since it has to support a much greater weight, and the ascent engine with a thrust of 3,600 pounds.

In a series of pre-programmed, controlled burns by the descent engine to slow the Lunar Module, the LM is first put into an elliptical orbit of 70 miles by 9.5 miles (50,000 feet), high enough to clear the Moon's mountains, and to bring it over the planned landing point at its pericynthion (the orbit's nearest point to the Moon), then a further braking burn takes the LM down to 9000 feet and oriented so that the crew can see and begin to evaluate the suitability of the landing zone. A further pre-programmed burn then takes the LM down to 500 feet at which point the crew must take over manual control of the descent.

Before landing, the crew were unaware of the precise nature of the Moon's surface and whether they would sink into a deep layer of dust. Depending on the nature of the terrain below, the pilot guides the LM away from any observed hazards such as boulders, craters, fissures and rock outcrops.

Real time feedback control from Mission Control of the final landing manoeuvres is not possible, even if it was desirable, because the two-way delay of a radio signals, travelling at the speed of light, carrying sensing inputs to Houston and responses back to the Moon is too long at 2.6 seconds and would result in instability and loss of control. (To this delay must be added the further delays introduced by the terrestrial signal networks).

At 500 feet the LM pilot Neil Armstrong takes control of the descent and makes any adjustments necessary, Finally, at 65 feet above the lunar surface, the the LM is re-oriented and descends vertically to the Moon at 3 feet per second and the engine is shut off as soon as the landing gear touches the surface.

Descending to the surface, the Lunar module was about 6,000 feet above the surface and the descent engine was halfway through its final 12-minute burn that would land the crew safely on the moon, when a yellow caution light lit up on the computer control panel. It was coded 1202, an "executive overflow" alarm, which meant the computer was having trouble completing its work in the cycling time available, and the astronauts asked Mission Control for instructions.

As NASA legend has it, 26 year old Steve Bales, the guidance officer (GUIDO) who had the authority to issue a Go or No Go decision on the landing - continued to issue a confident "We're Go!" throughout the remaining seconds of the descent, even as the 1202 and a similar alarm, the 1201, sounded intermittently. When the lunar module made its landing, it had seconds of fuel remaining before it would have to abort. The icy calm of Bales is a dramatic, iconic moment in NASA history, but as you peel back the layers of preparation that led to those moments, the story becomes almost astounding.

Bales who later accepted the NASA Group Achievement Award from President Nixon on behalf of the entire mission operations team credited his quick decision to an even younger whiz kid, John R. "Jack" Garman, 24 years old, an expert in the guidance computer software. It was Garman who, a few months before Apollo 11, gave the simulation supervisor, Dick Koos, the idea of testing the reaction of flight controllers to computer error codes. He also supported flight controllers in Mission Control as a backroom advisor on computer systems. By the time the actual landing was being attempted by astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin, Garman knew almost instinctively that a single 1202 or 1201 alarm did not mean the mission had to be aborted; it simply meant the computer was struggling to keep up. As long as the alarm did not become continuous, which would have meant that the computer was not getting any work done and vital tasks were being neglected, it would not prevent a landing.

And it was Garman supporting Bales from another console to whom Bales turned when the 1202 alarm went off. Quite frankly, Bales later recalled, Jack, who had these things memorized, said, Thats okay, before I could even remember which group [the alarm] was in.

For his part, Garman gives credit for his memorisation of the alarm codes to Gene Kranz, the fiery Flight Director who brough the Apollo 13 astronauts back to Earth after the explosion in their spacecraft. [Before the mission] Gene Kranz, who was the real hero of that whole episode, said, No, no, no. I want you all to write down every possible computer alarm that can possibly go wrong. Garman did so, along with the correct reaction to those alarms and kept this handwritten list under glass on his desk.

Searching for landing space in boulder field Apollo 11 Lunar Module touched down with only enough fuel and oxidiser in its tanks for a further 25 seconds of flight.

Armstrong and Aldrin alight from the LM and remain for two and a half hours of Extra Vehicular Activity (EVA) on the Moon during which they collect 22 Kg of samples of lunar rocks and soil as well as samples of the solar wind (charged particles emitted by the Sun) to bring back to Earth. They also take photographs and set up experiments to investigate soil mechanics and lunar seismic activity and they deploy a laser ranging retroreflector to enable precise measurements of the distance between the Earth and the Moon.

After 21.5 hours parked on the lunar surface, the crew fire up the LM Ascent Stage to return to the CSM mother ship leaving the Descent Stage on the Moon.

The Lunar Module Ascent Stage didnt need to accelerate to the Moon's escape velocity of 5,300 mph to leave te Moon. it only had to reach a lunar orbit with a velocity of 3,600 mph to rendezvous and dock with the CSM. The CSM provides the thrust to escape from the Moon's gravity. The main engine of the ascent stage takes the LM up to over 11 miles and puts it into an elliptical orbit.

There is no contingency plan if the Ascent Stage fails to get off the ground.

To rendezvous with the CSM, the LM executes a series of burns by its reaction control thrusters, controlled by the LM computer on the basis of data supplied by Houston Mission Control, that initially put it into a circcular orbit at an altitude of 69 miles concentric with the CSM, and then slowed it down to dock with the CSM. The LM commander takes over control for the final docking manoeuvre.

Return docking is very critical and difficult.

The crew return to the Command Module and the hatch is sealed.

The LM detaches from CSM which fires its reaction control thrusters to ensure complete separation. The LM Ascent Stage is left in lunar orbit.

The CSM main engine fires for 2.5 minutes to increase its velocity from 3,600 mph to 5,500 just over the Moon's escape velocity to break out of lunar orbit and send the Apollo 11 on a trajectory back to Earth. Like the Lunar Orbit Insertion, this manoeuvre takes place when the CSM is behind the Moon and out of communication with Mission Control.

Apollo 11's return voyage to Earth powered by the Eath's gravity. The gravitational effects of the Trans Lunar Coast are reversed. The velocity of the CSM initially slows due to the gravitational pull from the Moon, but as the spacecraft moves away from the Moon, the Moon's gravitational effect diminishes while and the Earth's gravitational pull increases. Once the Earth's gravitation becomes dominant the spacecraft is accelerated in a freefall all the way to the Earth reaching a velocity of 25,000 m.p.h. as it enters the Earth's atmosphere over three days later.

Similar to the outward journey, the velocity and angle of approach to the Earth must be very precisely controlled to ensure capture by the Eath's gravity and splashdown in the designated area.

Shortly before entering the Eath's atmosphere at an altitude of 400,000 feet (around 75 miles) the Service Module iss jettisoned by simultaneous firing of the reaction control thrusters in both the Service Module and the Command Module. The Command module is then rotated by 180 degrees to turn its blunt end towards the Earth.

Landing is just as dangerous as taking off and the precise re-entry trajectory is critical to making a safe landing. Once initiated there is no possibility of a second chance by "going around" and trying again if things go wrong.

The initial drag of 0.05 g experienced as the capasule enters the atmosphere triggers the Earth Landing Subsystem (ELS) which controls the re-entry process.

The Command Module enters the atmosphere, blunt end first, at 400,000 feet with a velocity approaching 25,000 mph at an angle of 6.5 degrees to the horizontal and flies about 1240 miles around the Earth to its designated landing point in the Pacific Ocean.

At the very high entry velocity the compression of the air in front of the capsule heats its surface up to around 2760 °C (5000 °F), hot enough to vaporise most metals, turning the capsule into a shooting star. A 2.5 inch thick, sacrificial ablative heat shield which burns and erodes in a controlled way carrying the heat away with its combustion products, protects the capsule from the heat of re-entry.

The only braking from the high re-entry velocity, down to the velocity at which parachutes can be deployed is by the drag of the atmosphere on the blunt shaped capsule. The reason for the 1240 mile trip half way around the world is mainly to provide adequate braking distance for the capsule, but also time for it to cool, by directing it along a sloping path through the atmosphere. Entering the atmosphere at too high an angle would either incinerate the crew or subject them to crushing g forces. In any case, in a normal landing the astronauts are typically subject to 6g. On the other hand, entering the atmosphere at too low an angle would not provide sufficient braking and the unpowered capsule would fly off into space with no possibility of return.

At the start of re-entry, the extreme heat of the shockwave generated by the compression of the air in front of the Command Module ionises the air creating a plasma which effectively blocks the transmission of radio signals to an from the spacecraft for about three minutes as it enters the atmosphere

By the time the capsule has descended to 24,000 feet, it has slowed to around 325 mph and a barometric switch initiates the jettisoning of the forward heat shield and the deployment of drogue parachutes which stabilise the craft, slowing its descent even further. At 10,700 feet. and travelling at 175 mph the three main parachutes are deployed reducing the Command Module's decent velocity to 22 mph for splashdown in the Pacific Ocean, just 15 miles from where the US Navy recovery ship Hornet is waiting for it.

The astronauts spend 21 days in quarantine as a precaution against the possibility of bringing back unknown pathogens from the lunar surface.

Hiçbir yazı/ resim izinsiz olarak kullanılamaz!! Telif hakları uyarınca bu bir suçtur..! Tüm hakları Çetin BAL' a aittir. Kaynak gösterilmek şartıyla siteden alıntı yapılabilir.

© 1998 Cetin BAL - GSM:+90 05366063183 -Turkiye/Denizli

Ana Sayfa / Index / Roket bilimi / E-Mail / Rölativite Dosyası

Time Travel Technology / UFO Galerisi / UFO Technology /

Kuantum Teleportation / Kuantum Fizigi / Uçaklar(Aeroplane)

New World Order(Macro Philosophy) / Astronomy